Please say my postcode 3280 aloud. What’s that? You said three two eight oh. Oh, shame, shame, shame. That fourth digit is not a letter—it’s a number. How about “3+2+8+0”? You said nought or zero—not the slightest hint of an ‘oh’. Why the compelling urge to mispronounce 0 when it is in a string of numbers? And so begins this diatribe which is naught but a grizzle about nought.

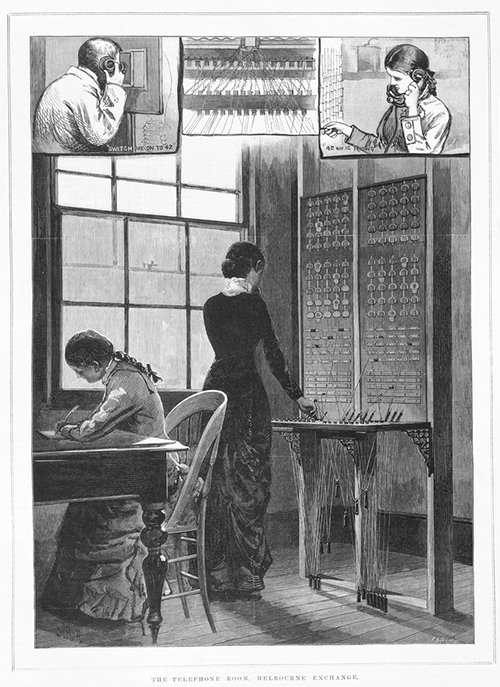

You may blame my oh-pedantry on a maths teacher who would condescendingly sneer ‘you are not a telephonist’ should oh pass anyone’s lips in class. Job-ism was alive and well in those days! But probably fair enough, since telephone numbers are certainly the greatest source of faux ohs. Triple oh, indeed. The military is not much better with a leading but unnecessary oh for an a.m. time, though ‘oh eight hundred’ commits an even greater numeric crime. Mr Bond possibly suffers the reverse problem: it is uncertain whether ‘double oh seven’ should simply be called ‘seven’ or written OO7 instead of 007.

Computer programmers quickly learnt that it was a big no-no to say oh instead of zero—so big they resorted to putting a slash through a zero, or a dot inside. It usually helped. My one free lunch when assessing mini-computers years ago was a valiant attempt by a salesman to keep me occupied while his boffins frantically tried to work out why my test program crashed their FORTRAN compiler so badly that the computer had to be rebooted. Its undoing was my innocuous but serendipitous “G0TO 50”.

Equating the slim ‘0’ to the fat ‘O’ insults one of the greatest advances in mathematics. Early drafts of Design for a positional decimal system simply left spaces in columns of numbers when there were no units or tens or hundreds. You can imagine how well such gaps would survive a newspaper editor’s urge to mangle columns of numbers by left justification (not). Fortunately, later drafts replaced those spaces with a symbol, which became our 0. It entered English from India via Arabia in two ways: as the word cipher (dated, and rarely used to mean 0) and the word zero. Nought came much earlier from the simple concept of nothing.

Why pick on 0 for gratuitous letter-calling? We don’t call 1 ‘eye’ or ‘el’, do we? Well, I suppose the Romans might have, and if they had had the nous to invent 0, ‘oh’ might be defensible. But they didn’t, which is probably ivtunviii, as my texting m8s might agree. And speaking of phones, it is ironic that you press 6 to generate an O, but 0 to generate the space it replaced so long ago—and 0 twice to generate an actual 0! *

Back to nought or zero. Which to use? Some of you may recall that the Ten TV network was once, in Melbourne at least, on Channel 0. “On the go with channel oh” was their catchcry. I delighted in saying this as “on the go with channel nought” but not “on the go with channel zero”, which at least rhymed if not scanned. That suggests the common usage was ‘nought’ back then, probably reflecting the choice between the US-preferred zero and the UK-preferred nought. Even so, there are a few exceptions where zero is accepted on bought sides of the Atlantic, countdowns being the best example: “… four, three, two, one, oh damn, I forgot to light the fuse”. I suspect that the chance of nought surviving the zero onslaught is zilch, nil, none, zip… which I’d better do, leaving you one last thought: might using ‘oh’ for 0 be just unacceptable familiarity in abbreviating (zer)o? And, if so, can ‘sev’ or 'levn' be far behind?

SERENDIPITY, WARRNAMBOOL

*The use of such ancient technology by someone who has worked with "mini-computers" and FORTRAN compilers should come as no surprise to the reader.

Telephonists of yore took great pleasure in misdirecting the calls of snobby maths teachers. The telephone room, Melbourne Exchange. Wood engraving by Julian Rossi Ashton 1851-1942. Published by Alfred May and Alfred Martin Ebsworth, Melbourne, January 29, 1881. State Library of Victoria, A/S29/01/81/37.